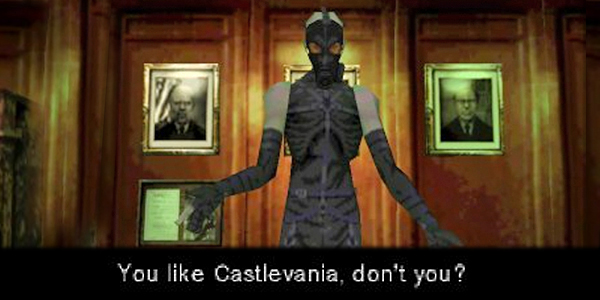

“You like Castlevania, don’t you?”

When I was a kid playing Metal Gear Solid for the first time, my encounter with Psycho Mantis left me totally speechless. I’d never encountered a game up until that point that directly spoke to me, the player, instead of the character I was playing as. It was a small, totally optional detail that was easily missed, but it was something that left my little mind blown for quite a while. I never encountered something like it until Eternal Darkness on the GameCube started to mess with my ability to play the game, once again directly interfering with me, the player, over the characters under my control.

As I grew up, I learned the term for this: metafiction, in which fictive texts break the fourth wall and directly interact with the audience, usually in ways that make the fact clear that things happening are truly fictional or part of some constructed reality. However, what caught me off guard was how infrequent metafiction was in video games compared to other media; metafictive novels, movies, and television shows are fairly common, but for video games, the trend towards metafiction is fairly recent, appearing heavily in the last twenty years of games or so.

Please note that some games discussed here may be heavily SPOILED! These games include: Umineko When They Cry, YOU and ME and HER: A Love Story, and Undertale.

Playing the Player

One issue, though, is that many modern games, including visual novels, rely heavily on metafiction for shock value, twists, or other narrative needs, reducing the game itself to something relatively unimportant to the meta-narrative being engaged with. Metafiction, perhaps more than any other type of genre, requires particularly keen sleight of hand and contextual knowledge to be effective; creators need to know their audience, their medium, and numerous other texts to come up with an interesting spin on the narratives they’re playing with, but an increase in metafiction also lessens the special, unique nature of these types of narratives—when more and more stories are meta, does meta even mean anything?

YOU and ME and HER: A Love Story is a particularly memorable game for exactly this reason: most players know the game because of its metafictive narrative, not because of any other reason; most players that have never experienced the game are likely drawn to it now by comparisons to Doki Doki Literature Club!, but also by its notorious reputation for breaking the fourth wall and engaging in horror-based meta-narrative storytelling. In some regards, this is almost unfortunate, as it means that the secret twist and shocking reveals of YOU and ME and HER are known to most people—even a casual look at the Steam page for the game reveals copious spoilers and hints of spoilers in the reviews. Without the surprise of what is to come, YOU and ME and HER is still an interesting game, but much of the narrative tension and suspense is gone; much like getting spoiled on the twist of a movie or book, revealing the fact that a game is going for meta-narrative tends to cause players to experience half of what the game wants to offer.

Meta Pitfalls

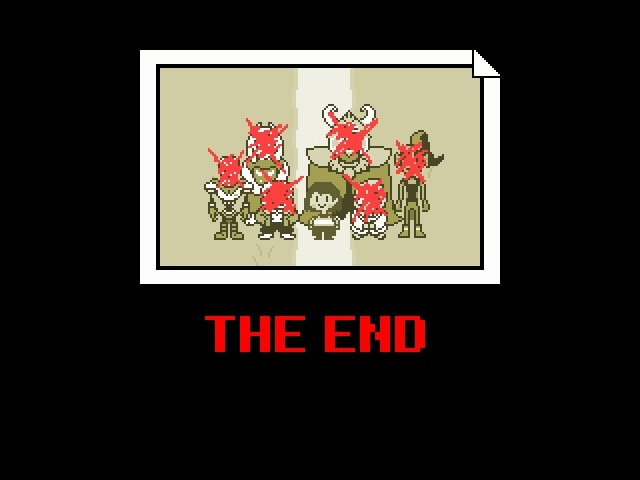

I have never achieved the Genocide ending of Undertale. I do know what happens, as I’ve seen it on YouTube and read about it, but I could never bring myself to play through it. In some sense, this might be a failure of meta-narrative game writing, as the sheer idea of experiencing such a route is so terrible to me that I just can’t bring myself to even try it. Or, maybe, that’s an indication of how powerful meta writing can be: the idea alone is so heartbreaking that I refuse to play a game I own in a certain way so as to avoid having to live through the experience itself.

Of course, the internet and the spread of instantaneous spoilers make these types of narrative twists hard secrets to keep, and in some ways dull their punch—I knew of the Genocide ending before I had even had a chance to finish Undertale at all, and thankfully avoided spoilers, but knew it existed. Even that gave me a “hint” as to how I should be playing the game to get the true ending, and that’s certainly one of the pitfalls of modern gaming discourse—creators can’t truly control player behavior, and meta-narratives like these become hot topics for YouTube videos, Wiki articles, and social media threads. While there’s no way for creators to combat this, it is something to consider when crafting meta-narratives—how long will your meta twist be a secret? What will happen when players know to expect it going in? Does it ruin the game altogether, or does it instead allow those players to expect something interesting and unique?

Similarly, while compiling a list of games to think about for this piece, I noted another trend: many meta-narratives, in video games and especially visual novels, tend to veer towards shock and horror as their general genres. There’s certainly a link between meta-narrative, which implies or makes the player/audience complicit, and mystery and horror, but since so many meta games veer in this direction, it becomes far less compelling the more and more it happens. When Doki Doki Literature Club!’s twists were revealed, players immediately started comparing it to YOU and ME and HER, debating whether one was ripping off the other. Undertale, too, veers towards shock and horror for the meta twists of the Genocide route, but other mediums don’t tend to do this with their metafiction; in fact, most comic books, television, and movies that work with metafiction tend to be comedies over horror, so why not meta games? There is certainly a market for these types of games, and visual novels especially that deal with meta topics have lots of ripe ground to explore, if only they’d take a step away from horror and visceral secrets.

Meta Meta Narrative

That said, when a meta-narrative pulls off the amazing reveal of implicating the player in some way, the game takes on an entirely unique and personal connection that can truly weave a compelling narrative. Umineko When They Cry does this by slowly revealing that the game is indeed a fictional story, being related to the player rather than events happening to the characters in the story itself; as the player gets further and further into the mysteries, this becomes more and more apparent, which then alters the way the entire series is read and presents itself.

Conclusion

Visual novels are a unique genre that requires immersing the player into their worlds in ways other games can only imagine, much more in line with prose novels than other forms of fiction. However, in terms of metafictive games, visual novels lag a little behind other forms of games that lean into including the player in things. There aren’t many comedic or even romantic meta-narrative games, and most of the games that do exist tread into the realms of suspense and horror over almost anything else. There is also just a lot of untapped potential for how fourth-wall breaking can make for more interesting narratives and experiences by deepening the immersion of the player into the story. It can also, however, run the risk of scaring off players, as their lack of knowledge may deter them from wanting to engage with the game since they may not “get” the meta-narrative hints and just find the game weird or boring.

As visual novels continue to develop, more and more metafictive attempts are likely to occur, whether they be small fourth-wall breaking jokes or reality warping narratives; these types of stories are increasingly popular in a world of always-on internet and instant connections, and in a world where audiences almost demand homages, references, and nods to other media and hints. For example, Marvel’s latest television shows, such as WandaVision and Loki, have articles and videos created within hours of their airing about “easter eggs,” hidden references, meta nods about Marvel media, and more. Visual novels, with the ability to blend immersive prose and personal, deep connections between player and game, are ripe for more and more meta-narrative stories to be told, but also need to avoid becoming stale or predictable—the next great meta-narrative game needs to try something different than Doki Doki Literature Club!, YOU and ME and HER, or even Undertale.

I wonder what visual novel will ever ask me if I like to play Castlevania?