From Charles Games comes Svoboda 1945: Liberation, a narrative game in Czech and English steeped in a deep mystery handed down from the past. In a small town on the border between the Czech Republic and Germany, the ripples of post-World War II trauma linger in every nook and cranny. What began as a historical assessment of an old schoolhouse and the feud it’s in the middle of, untold secrets and decades-old troubles bubble to the surface. Who can tell you the truth? What is the truth? The answer to either is not so easy to determine.

A review copy of this game was provided by the developer previous to public release.

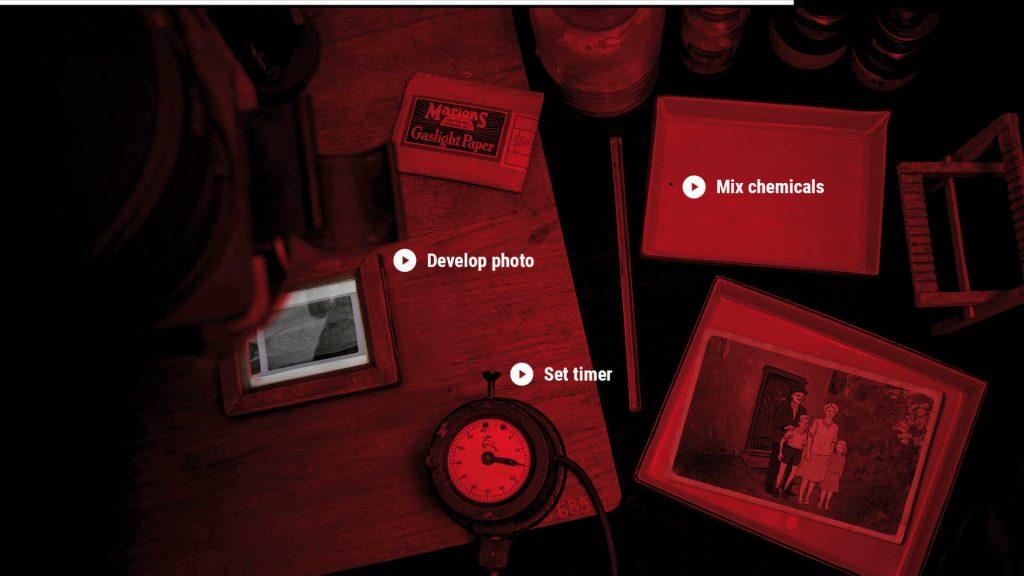

It is so hard to pin down exactly what kind of game Svoboda 1945 is. Its macro narrative delivery follows the basic conventions of a visual novel, and that’s the medium I would most equate it to. You’re engaging with text, you’re making choices that affect how the story unfolds in certain ways, and everything is, in a broad sense, scenically presented the way one would expect from a visual novel, with a particular emphasis on the visual aspects. But then, briefly, you’re playing a point and click as you decide what the government allows you to pack for your expulsion. Or you’re dropped, for just a few rounds, into a hopeless, collectivist farming simulator where things just get more dire each year. Where, in some games, this might read as a lack of gameplay focus, here it’s so deftly implemented, it feels refreshing. Instead of finding itself restricted by genre labels, it focuses on the story it wants to tell and the best way to do so ludonarratively. The result is both an extremely complex visual novel/adventure game hybrid and something just a little more than both those things that acts as an excellent example of what the medium can be with some out-of-the-box thinking.

Much of this comes from its choice in art and visuals. Eschewing the typical “sprite on background” or other illustrated art that’s common in this type of game, the story is instead told through a series of prerecorded video clips with screen actors. You’re faced with these real people in these real settings providing these incredibly emotional and sincere performances. When you ask them questions via selecting text, there’s a visceral response because it’s an actual person reacting to you. Between these segments and the more interactive point-and-click portions, memories and recollections unfold through these short interactive comics. They’re only a few panels each, but they encapsulate so much energy and emotion that even when you can tell there’s some reuse of assets, each segment feels transformative on its own.

What this game does so excellently is drop you in the middle of this vast narrative experience and immerse you in it completely. It sets you right down in the middle of this great convergence of story lines that span both early aughts and post-World War II Czechia. It’s this wonderful storytelling in parallel where past and present exist simultaneously as the story of this small town and the people who live there unfold. Every mystery and secret uncovered, yours included, is this new puzzle piece that shifts and retells the story from a new perspective, and you’re positioned right in the middle of it every step of the way.

And this story that you’re right in the middle of is this maelstrom of tragedy and uncertainty and upheaval in a world that’s been torn apart by war and is barely keeping it together—and frequently isn’t keeping it together. It’s a story with a lot of gray area. It dares to ask the question “when the main villain is defeated, who’s the bad guy now?” More importantly, it doesn’t answer that question. It knows that it can’t, so it brings you face to face with people that force you to confront that fact head on. In the end, you have to decide what’s more important: preserving the past for all the good and ill, or focusing on the present and the future that comes after. In the end, it’s not an easy choice to make.

Svoboda 1945: Liberation is a story of war, but not of battles or military campaigns or politics. It’s a story about the people of war. Imperfect, uncertain, morally ambiguous people. Some who are running from their past, some who think abandoning it will do more harm than good. It’s raw and heartbreaking, but there’s this glimmer of hope that runs through it. That despite all the horrible things these people went though, they’re still living. They’re surviving. It all comes with both a promise and a threat that the past can’t stay hidden forever, for better or ill.